Chapter 7

Transcription and

Transformation, 1946–1949

The period began with

headlines on the front page of Variety magazine’s first issue of 1946

illustrating the extent of Bing’s success.

Bing’s

Bangup Box Office in ’45

400G

from Decca Records alone

No other figure on

the show business horizon has managed to parlay his multiple pix-radio-music

talents into the gross yearly earnings wrapped up by Bing Crosby during 1945.

That he’s the hottest guy in show biz today is reflected in the unprecedented

royalties (more than $400,000) from the 1945 sale of Decca records. Add to that

the current jockeying among every top advertising agency in the business and

the top bankrollers in radio to latch on to Der Bingle’s radio services in the

wake of his Kraft Music Hall divorce, plus the record four-week grosses racked

up by the Radio City Music Hall, N.Y., for his current starrer, “Bells of St.

Mary’s” (those 7:30 a.m. lines of customers circling the Rockefeller Center

theater building have been one of the top attractions for New York holiday

oglers) and you can credit El Bingo with copping, hands down, all laurels for

emerging the one-man industry in show biz today.

As

Decca’s all-time disk grosser, the Groaner has recorded during the year

virtually every pop song that struck the public’s fancy. It’s by far the top

royalty slice to any disk performer in modern times, and maybe of all time,

with the current Crosby fan wave making him even potentially bigger in ‘46. . .

.

Crosby

is said to have a royalty deal with Decca which gives him 10% of the retail

price of every record sold (his disks retail at 50c). On that basis, the 400G

royalty total indicates that some 8,000,000 of Der Bingle’s needlings went

across the counter and into jukeboxes in 1945. That’s considerably in excess of

the number he must sell in order to earn the $300,000 he’s said to be

guaranteed annually by Decca.

(Variety,

January 2, 1946)

While this sounded

marvelous, it was also true to say that Bing was increasingly beset by

difficulties all around him. The issues at home with Dixie’s drinking were

continuing, he may well have been engaged in an extramarital relationship with

Joan Caulfield, his health was affected by his kidney stone problems, he was

locked into a legal dispute with Kraft, his singing was reflecting the

uncertainties in his life and, incredibly bearing in mind his income, he had

cash flow considerations to worry about too.

The long-running

Kraft contract duly ended after the legal battle as Bing fought to have the

right to record (or “transcribe” to use the jargon of the times) his radio show

in the same way that he had previously recorded broadcasts for the armed

forces. He moved to Philco in 1946 and problems emerged not only with the

recorded show, but also with Bing’s voice which had fallen from its previous

high standards. However, Bing came back strongly in 1947 after his troubles and

he regained his vocal prowess, albeit with a narrower range in a lower key. His

record sales were aided considerably by Decca issuing 36 albums of his

songs during the years 1946-49. Many were repackages of earlier

releases although some contained new recordings. Initially issued as

78rpm albums they were also released as 10" long-playing vinyl records when that

format was introduced during the late 1940s.

The

Philco show achieved good ratings although the impact of television was

becoming apparent. A switch to Chesterfield in 1949 kept Bing in the forefront

as a radio star, but the medium was undoubtedly starting to lose out to

television as the decade ended.

Although Bing’s

income had indeed been enormous during the 1940s, his net income had not been

well managed by his brother Everett and on his attorney’s recommendation, he

recruited an accountant called Basil Grillo from Arthur Andersen to restructure

his financial situation and find more tax effective ways of earning money.

During the war, the special income tax levied on American citizens to fund war

production and mobilization had taken over 90 percent of Bing’s income and

although tax levels reduced, they were never to return to prewar levels. He

sold his interest in the Del Mar Turf Club and rolled the funds over into a

share of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team. His home at Rancho Santa Fe was

sold and he increased the size of his working cattle ranch in Nevada. In 1949,

he raised a large sum of money when changing radio company from ABC to CBS and

he went on to invest lucratively in oil wells.

Bing spent a

considerable amount of his time away from his Holmby Hills home and he and

Dixie were infrequently seen together although the myth of the happy marriage

was maintained. He tried to spend periods with his sons whenever possible and

each summer he took them to his ranch at Elko, Nevada, and then on to a holiday

home at Hayden Lake, Idaho.

After being

suspended during the war, his annual golf tournament was relaunched at Pebble

Beach in 1947.

Commercially the

1940s belonged to Bing but, after the war, it was apparent that the huge

pressures on him from various sources had transformed him into a more

introverted personality and he started to avoid live appearances and social

events. A trip to Vancouver in 1948 brought him back into contact with a large

unruly crowd again and the local press carried a perceptive article which was

probably fairly close to the truth. The article is reprinted courtesy of The

Vancouver Sun.

Bing

Puzzled Over Mass Hero–Worship

Man

Forced into Limelight Glare Prefers Shadows of Private Life

Bing

loves ‘em individually; but collectively people are perhaps his greatest

problem. His life, say those who know Harry Lillis Crosby, is one long pursuit

to “get away by himself and be natural.”

Semi-retiring,

genuinely friendly, taken aback by crowds, “a man of more depth than most

people give him credit for”—that’s Bing, say his friends. And yet few

personalities on the Canadian-American scene are so surely calculated to draw

crowds wherever they go. That’s Bing’s quandary. The whole show company

traveling with him are well aware of his allergy for crowds, though few admit

it. Hence the public find this company, constantly “running interference” for

him.

Bing,

meanwhile, keeps as few formal appointments as possible, although he is always

punctual when committed, sings and jokes his programs, then runs “to get away

from it all.” Then he is likely to show up a few minutes later at a boys’ club,

or on a sandlot pitching the ball with the kids.

“He

realizes the responsibility grown-ups have to youth. That’s why he’s here,”

said one of his company.

“People

love Crosby. But when they show it in such large numbers he seems actually a

little frightened. Bing likes people too. But he doesn’t like crowds.”

But

crowd conscious or not, he is still the day-to-day quarry of a relentless horde

of idolizing youngsters who want his autograph, wide-eyed women who want to

“just pinch him,” men who tell him they think they have a voice, etc. In

Vancouver, something new has been added. An English inventor traveled all the

way here from the Old Country to see Bing. He wants the crooner to sponsor the

manufacture of a new-type auto trailer. Life’s like that for Bing “a little guy

who likes people, but not crowds.”

(Bill Ryan, The

Vancouver Sun, Wednesday, September 22, 1948)

However, despite

all of his problems, Bing generally managed to continue to maintain his public

image of the easygoing crooner, and as a film star, he was the top box office

performer for a record five years. This, allied to his vast record sales, his

highly-rated radio shows and the constant publicity made him, arguably, still

the most famous man in the world for most of the period.

In 1949, $100 was

equivalent to $721 in the year 2000.

1946

January 2, Wednesday.

John O'Melveny and Everett Crosby join Bing in New York. Bing sends a

telegram to J. Walter Thompson stating that he will not return to the

Kraft program on January 3 as requested. In the early afternoon, he

goes for a brisk walk and meets the Barsa girls (two young fans) and

takes them for a frankfurter at Howard Johnson's.

January 3, Thursday. Kraft

files suit against Bing as he will not complete his Kraft Music Hall

commitments. The process server hands Bing the summons as he opens the door to

his New York hotel suite. It is revealed that Bing has been receiving $5,000 a

show since 1939.

January 5, Saturday. Bing

attends the opening night of the revival of Show Boat at the Ziegfeld

Theater in New York.

January 7, Monday.

Dixie’s

mother, Nora Matilda Scarbrough Wyatt, dies from a heart attack in

Santa Monica at the age of 63. There is a private service at 2 p.m. at

Pirece Bothers, Beverley Hills on January 10 and she is buried at

the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, Los Angeles the same day.

January 9, Wednesday.

Rumors about Bing's relationship with Joan Caulfield are starting to

circulate and in an effort to calm these, he writes to Hedda Hopper

stating that he and Joan have a very firm friendship and that there is

nothing clandestine about the relationship. However around this time he

goes to see Archbishop Spellman and tells him of his marital

unhappiness. Spelllman makes it clear that divorce is out of the

question and recommends that Dixie is put into a sanitarium as soon as

possible.

January 12, Saturday. After

indications that the dispute between Bing and Kraft was to be settled amicably,

John Kraft changes his mind and decides to go to court.

Round And ‘Round Kraft

And Crosby

Dispute between Bing Crosby and

Kraft Foods over former’s desire to ease out of his Kraft Music Hall contract

which seemed likely to be settled amicably, last week, after several huddles

between representatives of both principals will now go to court due to a

reported, last minute, change of heart on Saturday (12th) by John Kraft. As a

result, Crosby’s attorneys are now preparing an answer to Kraft’s application

for an injunction.

Kraft

claimed Crosby has reneged on a 1937 contract which it states runs on until

1950. The Groaner, however, maintains that last summer when he gave notice to

quit, he was merely taking advantage of California’s seven-year employee law

which says an employee can’t make a contract beyond seven years. In its

application for injunction, Kraft acknowledges the Crosby statute but maintains

that Crosby was not an employee but an independent contractor. This claim is

based on the fact that Crosby himself picked the four songs which he sang on

the Music Hall program each week. Crosby denies he’s a contractor, pointing out

that he hired no one for the program, merely presented himself and used Kraft

scripts handed to him. He also maintains that his weekly Kraft pay check had US

Withholding Tax deducted from it, proving that he was an employee.

Furthermore,

according to Crosby, Kraft Foods promised that they wouldn’t go to court over

the matter but would sit down and discuss it first. Crosby or his manager

brother, Everett were in constant touch with Kraft or their agency, J. Walter

Thompson. They came East, three weeks ago, after John Kraft, in Chicago, phoned

them to do so, to thrash the matter out, then the injunction application was

filed. Despite this, according to Crosby, the two sides met amicably. Crosby

offered to do two broadcasts while Kraft countered with a request for

twenty-six broadcasts before they would release him. Crosby came up to six,

Kraft replying it would take the six now, with five more guest shots, next

Fall. Crosby countered with an offer to do thirteen broadcasts and two guest

shots, next Fall; whereupon, according to Crosby, Kraft reps asked for thirteen

now and four guest shots in the Fall. This was the situation last Thursday.

On

Friday, after consultation with John Kraft, in Chicago, according to Crosby,

their offer was withdrawn. Kraft reverting to their original for twenty-six

broadcasts, whereupon Crosby decided to go to court.

(Variety, January 16, 1946)

January 14, Monday. The annual

Photoplay Gold Medal Awards formal banquet takes place in the Palm Room of the

Beverly Hills Hotel. Bing has won the Gold Medal for the most popular actor of

1945 as determined by the Gallup Poll of America's moviegoers. As he is still

in New York, his mother accepts the award on his behalf.

January 15, Tuesday. Bing

attends a party at Eddie Condon’s apartment in Washington Square which goes on

until the early hours.

January 16, Wednesday. (10:00

a.m.) The Eddie Condon band meets to rehearse with Bing at Condon’s apartment

in New York. At 3:15 p.m., Bing arrives at the Decca’s Studio A in New York and

between 3:45 p.m. and 5:15 p.m. he records three songs with Eddie Condon,

including “After You’ve Gone.” A different pianist is used for each song with

Joe Bushkin accompanying Bing on “Personality.” The latter song enters the Billboard

best-sellers chart for three weeks and peaks at No. 9.

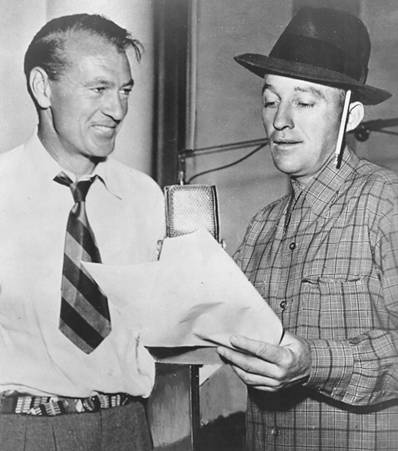

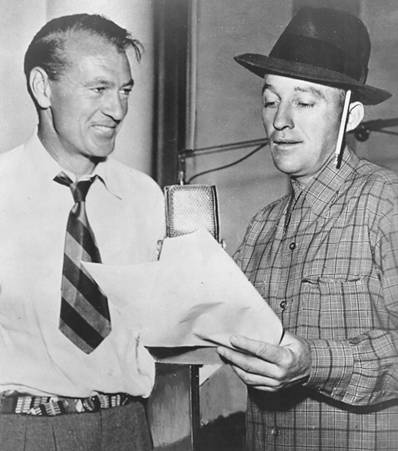

The old studio clock had just struck

3 p.m. Condon’s barefoot-boys-with-shoes-on were on hand but showing visible

signs of strain at the early hour. Decca types hustled—keeping a sharp eye on

the door. At about 3:15 p.m. the Crosby arrived. Stripped of his bright yellow

scarf, tweed coat, and inner-lined battle jacket, he was left naked in a brown

felt hat, bright red checked shirt, brown slacks, and the sort of shoes

ordinarily seen in the Alps at this time of year. Came 3:45, and in rushed

Condon. No taxis, he said.

“Blue

and Broken-Hearted,” the first number to be waxed, didn’t go so well. A large

blue screen-like sound absorber stood between Bing and the boys. Kicking it

aside, he commented: “Got to see if anybody’s alive out there.” Another

run-through or two and, at his question: “Will this be the deathless disk?

Shall we, men?” the side joined history.

“After You’ve Gone,” went rather quickly. Although trouble loomed when Jack

Kapp, president of Decca and Crosby-adviser-extraordinary on record policy,

walked in and asked if “Wild Bill” Davison’s trumpet ought to stay so dirty.

“You go back to the board of directors if you make one more remark,” Crosby

said. “I’ve flown these boys in at great expense. Eddie flew in without a

plane.”

The

clock was falling away from 5 when the group assailed “Personality,” a sock

potential from “Road to Utopia.” Since Dorothy Lamour sings it in the picture,

Bing had never seen the music. But no matter. He smoked his pipe (“the kinda

singing I do, you can’t hurt your voice”), achieved one of his rare grimaces at

what he called Newsweek’s “nostril shots”, and the side was done. Exit the Crosby—fast.

(Newsweek, January 28, 1946)

January 21,

Monday. Bing

records “On the Sunny Side of the Street” and “Pine Top’s Boogie

Woogie” with

Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra. Hampton subsequently announces that

he will give half of his royalties from the recordings to the Sister

Kenny Foundation in which Bing is heavily involved. Bing goes to see

the New York opening of Nellie

Bly at the Adelphi, Broadway. Marilyn Maxwell has been replaced by Joy

Hodges and the play has been extensively revised. The reviews are again poor

and a “notice to close” is posted after the first week. The show closes after

sixteen performances on February 2. Bing is reported to have lost $50,000 on the production.

On the Sunny Side of the Street

It’s only

because of the combination of the Groaner and the Hamp that the side is bound

to attract undue attention, both in coin boxes and across the counter at the

retail marts. And while Crosby’s chant may not be in the groove, Hampton’s

music definitely is. Moreover, the vibe pounding maestro provides some of the

lyrical joshing that Crosby fails to deliver. Flipover is a solid eight-beat

rider in the classic “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie,” which features Hampton’s flash

knuckling of one or two fingers on the keyboard while Crosby staggers thru a

prepared script with stop-and-go boogie woogie exhortations.

(Billboard,

June 14, 1947)

NELLIE BLY

Story Synopsis

Frank Jordan, managing editor of the

New York Herald, is excited by the threat of a promotional beat staged

by the New York World. The World assigns a reporter, Nellie Bly,

to circle the globe in an attempt to beat the eighty-day record of Jules Verne.

Jordan of the Herald engages Phineas T. Fogarty, who has been working as

a “stable boy for the Hoboken Ferry,” to race Nellie. To be sure Phineas

doesn’t loaf on the job, Jordan goes along and manages to fall in love with

Miss Bly before the evening is well started.

Review

It is reliably reported that the

musical show, Spring in Brazil, which failed on the road to the tune of

300,000 dollars and was not brought to New York, suffered from so much

rewriting that by the time it reached Chicago the only line remaining from the

original book was properly enough, “Good God, what an awful mess!” The

insistence of the grimly vengeful leading comedian, Milton Berle, is said to

have been responsible for its retention, a compromise having being effected

with the show’s understandably obdurate producer in the elimination of the

qualifying adjective “awful.”

It is

also reliably reported that this Nellie Bly, which was nevertheless

brought into New York and failed to the same 300,000 dollar tune, underwent so

much outside rewriting that the original authors, the Messrs. Ryskind and

Herzig, wrathfully severed all connection with it on the road when the

management declined to permit them to incorporate the line from Spring in

Brazil. Just what the natal shape of the show was, I have no direct

means of knowing, but it may be allowed from first-hand observation that one of

the two dozen or so final troubles with it was that most of the people

connected with it did not seem to know in the least what they were talking

about. . . . Mr. Cantor, co-producer of

the show, who supplied the major portion of the 300,000 dollars wasted on it,

is further said to have been infected to the point of inserting into it divers

additional humors which he esteemed as irresistible novelties and which

amplified Mr. Moore’s notion of sumptuous belly-laughs. As examples of their

unsurpassed novelty may be cited a scene in which Mr. Moore was disguised as a

harem siren and was made love to by an actor who believed that he was a female;

another in which Mr. Moore stuffed his laundry into his bosom and observed that

if he was going to drown in the sea he might as well get it washed free; still

another in which Mr. Moore proclaimed that if he was lying to his female

companion might St. Patrick send down a bolt of lightning and strike him, with

the bolt promptly serving as a blackout; another still in which the desperately

seasick and undone Mr. Moore was told “You give up too easily,” with his

retort, “I’ll say I do!”; another yet in which Mr. Moore, carrying a pail of

beer, was apprised that “It has a head on it” and his inquiry, “Is it anybody I

know?” and such jocosities as “There’s a south south-easter blowing from the

north-west.” . . . Nellie Bly found itself in the unfortunate

predicament of going around the world backwards.

(George Jean Nathan, from The

Theatre Book of the Year, 1945-1946)

January 22, Tuesday. Records

with the Jay Blackton Orchestra in New York including the songs from Nellie

Bly. Bing is in poor voice but his version of “They Say It’s Wonderful”

reaches the Billboard Best-Sellers lists and spends four weeks in the

charts with a peak position of No. 12.

January 24, Thursday. Everett

Crosby announces that a settlement has been reached with Kraft Foods Co.

following out-of-court negotiations. Bing leaves by train for the West Coast.

Ed Sullivan Speaking

What

persuaded Bing Crosby to drop from the air? Why did he suddenly

decide that he’d do one program a month, instead of one a week? Everybody has

guessed at the reason. Instead of guessing, I asked “The Groaner” how the

litigation with Kraft started.

“It’s

simple, Ed,” said Crosby. “I got the idea as a result of those ‘Command

Performance’ broadcasts we did for the troops overseas. It dawned on me then

that the proper way to do a broadcast was to first play it before a studio

audience, and learn from them what jokes to cut out, what songs to sing. Then

when the thing is letter perfect, put it on a record. If the first record isn’t

top-notch, well — break it, and make another record until you get exactly the

pace you want. You rarely get a perfect studio broadcast to send out over the air.

I think that a recorded program is the answer and correction of all the human

errors that are inevitable in a studio broadcast.”

Before he

left New York and went back to the Coast, Crosby made at least a

dozen records for Decca’s shrewd, able Jack Kapp. . . . Largely, they were

Irish records. One of them you’ll be hearing is “Dear Old Donegal,”

which Bing made with the Jesters and a hot band fronted by Bob

Haggart. This number happens to be Pat O’Brien’s favorite, and Pat sings it at

the drop of a shillalah. So Kapp and Bing determined that at some

point in the lyric, they’d have to work in a reference to their pal, O’Brien.

When you hear the record, as Bing reels off a list of Irish names,

you’ll hear one phrase: “And Pat O’Brien showed up late.”

Just how

many records Crosby has made since he first plattered “I Love You

Truly” and “Just A’Wearyin’ For You” back in 1934 would require a staff of

CPAs. I asked Kapp, instead, what records had won the greatest sales. Out in

front is Bing’s Decca platter of “White Christmas,” which sold 2,500,000 in

this country, plus 500,000 abroad. Second would be “Silent Night,” with a sale

of 2,000,000.

(Ed Sullivan, Modern Screen,

April 1946)

January 25, Friday. Bing tops

the list of nominees for the “Best Actor” Oscar for his role in the film The

Bells of St. Mary’s. The results are to be announced on March 7.

January 28, Monday.

Bing arrives back in California on the Santa Fe Super Chief having

played gin rummy all the way from Chicago to Pasadena with Spike Jones.

On his return, he tells Dixie that

unless she stops drinking, he will seek a legal separation and her

partial custody of the children will depend on her ability to take care

of them properly.

Wearing a screaming

cravat and looking as if he were on the rough end of 30-day diet, Bing Crosby stepped

from the Super Chief into the bright California sunshine at the Santa Fe depot

in Pasadena yesterday morning. Bing, who likes a riot of color in his attire (the

tie would indicate that he has a strong preference for pink), was returning

from a six-weeks’ stay in New York. He arrived at 8:45 a.m., which may have something

to do with his wan appearance. No doubt about it, though, Der Bingle has lost

weight, and it shows up mostly in his face, which is no longer round.

(Bill Bird, Pasadena Independent, January 29, 1946)

…a field day in Pasadena, with Bing Crosby, Spike Jones,

Gloria and Joan Blondell and Johnny Burke getting off the rattler. Their

arrival in Pasadena ended a 19-hour gin rummy game for Bing and Spike. They

started playing when the train pulled out of Chicago, and when they totted up

the score Bing had won $1.25. Six cents an hour…

(Daily Variety, January 30, 1946)

January 31, Thursday.

Bing makes an appeal for contributions for the Sister Kenny Campaign

which is still struggling to reach its $5m target.

February 1, Friday. Bing

attends a meeting with Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett regarding the

forthcoming Emperor Waltz film. Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke are

also present. Wilder indicates that he thought that some of the songs

written for recent Crosby films were weak. A problem arises with the proposed

inclusion of “I Kiss Your Hand, Madame” but eventually agreement is reached.

February 4, Monday. Bing and

Bob Hope are featured on the cover of Life magazine.

February 5, Tuesday.

Bing replies to his friend Father Corkery's letter about the situation

with Dixie. Corkery had also ruled out divorce and suggested that Dixie

had treatment. Bing indicates that he is reluctant to place Dixie into

a sanitarium.

Dear

Frank,

Mother

called me just before I left New York and told me there was some chance your

Los Angeles visit might be extended a day or so. I was hopeful of finding you

here upon my arrival, but I can well appreciate that more important and vital affairs

called you to Spokane.

I’m glad

you took appointments to meet my wife and children, even if the visit had its

unpleasant aspects. She was once a wonderful girl, and basically, is still a

highly moral person. Unfortunately this appetite is a little too strong for her

and has produced a split personality. The history of her case, of course, would

take much more time than I would care to devote to it in a letter, and when you

return in April (as you indicate you intend) I’ll supply the dreary details. I

have no definite plans. This kind of a situation defeats planning. All I really

know is that it’s impossible for me to do the amount of work my responsibilities

require me to do, and abide this kind of a life at home.

I saw

Cardinal Spellman in New York, and he told me the most important thing was to

put her in a sanitarium at once. That the children should not be daily witnesses

to what generally transpires. But she would have to be placed there by force,

and being a very proud person, I am sure would not long survive such a move. Or

if she survived, past experience hardly provides hope that she would be cured.

Since

returning home, I've taken one step. I have told her that unless she improves I

shall have to arrange a legal separation, and her partial custody of the

children will depend on her ability to take care of them properly. This has

frightened her some, and some improvement can be noted. The local newshawks

have long heard the rumblings and smell a story - as a result every step must

be carefully taken, and every precaution employed. I propose

to go along on this line a few weeks and see what develops. I don’t start a

picture for about a month, and am thus able to spend a great deal of time at

home, which is a good thing, even if sometimes unpleasant.

It’s

constantly amazing to me what a tough time these Crosby boys have with their

wives. I guess our mother, by her example, led us to expect too much. I know I

spoiled Dixie for the first eight years of our marriage. She had too much

leisure, too much money, and lacked the background or experience to handle it.

I’ll

look forward to your visit in April.

Your

friend,

Bing

February 7, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show in NBC Studio B in

Hollywood. (6:00–6:30 p.m.) Bing returns to the Kraft Music Hall radio program for thirteen shows

under a compromise to break the contract. Ken Carpenter, the Charioteers, Eddy

Duchin, Frank Morgan, and John Scott Trotter and his Orchestra continue as

regulars on the show. Audience share for the season overall for the Kraft Music

Hall is 17.5 pushing the show down to twentieth position in the ratings. Bing’s

absence for several months had obviously had an impact. The top evening show for

the season is Fibber McGee & Molly with 30.8.

THE MAN WHO WALKS ALONE

Bing Crosby, a man who walks alone, walked back

into his radio program in characteristic style this week. After months of

arguments and a law suit, Bing came back to his old stand at the Music Hall.

More than the usual number of songpluggers–about 45–were at NBC studios to

press their tunes on him. He walked right through then, tossing a nonchalant

greeting to those he knew.

He sauntered

into studio B, waved a casual “Hi kids” as though he had been gone 15 minutes

and sat down on a stool by his microphone. The rehearsal began and things

looked normal in the Music Hall again. Bing had his regular loud sports shirt

hanging over his slacks and the pencil was tucked under his hat. John Scott

Trotter supplied a downbeat and the world’s most famous voice began to wave its

charm.

(Bob Thomas, Hollywood Citizen News,

February 9, 1946)

Bing Crosby slid back into his old,

Thursday night NBC slot, last week (7th) and once more everything’s as it

should be on Kraft Music Hall. His belated entry into the ’46 programming

sweepstakes automatically provided nighttime radio with a hypo. A half-hour

with El Bingo and it’s easy to understand why his sponsor made a super

production and a federal court case out of his exit threat.

The

Crosby style provides for a final thirteen week, smash semester for the Groaner

on Kraft Music Hall, after which he’s privileged to talk terms with anybody but

latest reports have it, that it is strictly within the realm of possibility

that Crosby will be back again on the Kraft bandwagon, next season with the

sponsor taking a cue from Texaco, willing to toss in a couple of cheese

factories or anything his heart desires which would appear to be to Kraft’s

advantage. Make no mistake about it, Crosby’s still got what it takes. It was

demonstrated, last Thursday, when he moved in on Kraft with a naturalness that

belied the months-old, bitter entanglements. Introduced as a guy just back from

vacation, he bantered and sang his way through the Kraft session with the same

casualness, ease and showmanship that have trademarked his picture-radio

career, in recent years. “Aren’t You Glad You’re You”; “I Can’t Begin To Tell

You”; “Personality” (from the Crosby/Bob Hope/Dorothy Lamour Road to Utopia

pic) and “These Foolish Things.” With his knack for keeping the palaver

rolling, here were the sock ingredients for a “boff” Crosby turn. As presently

set up, however, the Kraft showcase is top heavy with talent and not without

its imperfections. For instance, there is Frank Morgan who’s been holding down

the spot since the start of the season; he’s committed to Kraft until June

which takes him right through the thirteen week period with Crosby. It’s

strictly a clash in personalities, there’s a discordant note about his

brashness that isn’t attuned to the Crosby tempo. Fortunately, the

scriptwriters were not over-sensitive in minimizing his contribution. On the

other hand, Eddy Duchin, also a regular on the show, since his recent return to

civvies, blended harmoniously into the stanza. In fact, the Crosby/Duchin

parlay shapes up as a natural, this season, next season, with or without the

Kraft auspices. His pianistics on ‘Where Or When’ and ‘It Might As Well Be

Spring’ was top drawer and complemented the Crosby mood. The Charioteers and

John Scott Trotter’s Orchestra gave an assist that was all in the show’s favor

and Ken Carpenter is still turning over those Kraft commercials, smoothly.

(Variety, February 13, 1946)

February 9, Saturday. Bing is the host for 450 wounded veterans at The Masquers dinner.

February 13, Wednesday. He receives the Picturegoer

Gold Medal Award from David Niven at the Paramount studios. The award by the British magazine Picturegoer is for Bing being voted "Britain's most popular star in 1945".

Bing, at least 20lbs lighter from

the combined effects of arthritis and worry – he has been going through

troubles apart from professional ones, and these are all his own business –

couldn’t take his eyes off the Gold Cup as it rested on the luncheon table

ready for the various guests…He is, however, a buoyant personality and a great

natural wit, and it is all the more regrettable to find him a bit off beam. His

health is improving, however. There is nothing seriously wrong, and everyone

hopes that other conditions around him may soon clear up so that he can feel

his own happy, carefree self again.

(W. H. Mooring, Picturegoer,

February, 1946)

February 14, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show in NBC Studio B in

Hollywood. (6:00–6:30 p.m.) Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests

include Les Paul. A song from the rehearsal is issued on V-Disc.

February 19, Tuesday. Press

reports state that Gary Crosby (age twelve) is taking off some weight at Terry

Hunt’s.

February 21, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Frank Morgan and Eddy Duchin are guests.

February 27, Wednesday.

Transcribes a special Command Performance Show for Army Day at the CBS Playhouse on Vine Street with Bob Hope,

Dinah Shore, Frank Sinatra, Bette Davis and the Andrews Sisters. Harry Von Zell

in the announcer and the show is broadcast on April 6. Elsewhere, Bing’s film Road

to Utopia has its New York premiere at the Paramount and goes on to take

$4.5 million in rental income in its initial release period.

That was a great command

performance for Army Day with Bette Davis, Bing Crosby, Bob Hope and Frank

Sinatra all on stage ribbing one another at one time. The C.B.S Playhouse on

Vine St. was packed. Others taking part in the big affair were Dinah Shore, who

emceed; Jimmy Durante, who had much fun with big words; Spike Jones, Meredith

Willson, Harry Von Zell, et al. Producer Art Van Horn was receiving plaudits.

(The Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1946)

Not since Charlie Chaplin was prospecting for gold

in a Hollywood-made Alaska many long years ago has so much howling humor been

swirled with so much artificial snow as it is in “Road to Utopia,” which came

to the Paramount yesterday. And not since “Road to Morocco” have Bing (Damon)

Crosby and Bob (Pythias) Hope been so crazily mixed up in madness as they are

in this current vagrancy. For the latest of Paramount’s “Road” shows, in which

the Messrs. Crosby and Hope again have as fellow-traveler the indestructible

Dorothy Lamour, is a blizzard of fractious sport and clowning, a whirlwind of

gags and travesty, a snowdrift of suffocating nonsense—and that is said without

consulting a press book.

There is no point in telling anybody what sort of

humor to expect when the Messrs. Hope and Crosby are turned loose together in a

show. Their style of slugging each other with verbal discourtesies is quite as familiar

as ice cream—at least to the patrons of films. And their can-you-top-this vein

of jesting runs straight through our national attitude. The only difference, in

this case, is that their style seems more refined, their timing a little more

expert, their insults a little more acute. Bing and Bob have apparently been

needling each other for so long that they naturally stitch along a pattern

which shapes the personalities of both.

And the personalities of the rascals—Bing the

debonair blade and Bob the bumbling show-off—are fully defined in this tale of

a couple of vaudeville grifters caught in a race for an Alaskan gold mine. Mr.

Hope is the chicken-hearted partner who wants to go back to New York; Mr.

Crosby is the adventurer who wants to woo fortune in the mining camps. And

that’s why (despite Bob’s demurrers) they find themselves in roaring Skagway,

holding a secret map to a gold mine which is really Miss Lamour’s by rights,

mistaken for two desperadoes and caught blindly between two villainous gangs.

Out of this lurid situation the Messrs. Crosby and

Hope—with the help of the boys at Paramount—have ripped a titanic burlesque of

brawny adventure pictures and of movies in general, indeed. A “Road” show is

always an occasion for the cut-ups to have a marvelous time and in this case

the comic inventors (stars and writers and director) ran wild. The late Robert

Benchley is employed as a sort of commentator on the film, who pops in the

frame at odd moments to give a goofy explanation of the cinema craft. Actors

from other pictures walk across the sets and the Messrs. Hope and Crosby

several times address the audience. And, of course, the whole nature of the

action is in the grand style of ha-ha ridicule.

But where this sort of clowning might be juvenile

and monotonous in other hands it has rich comic quality in the smooth paws of

the gentlemen involved. To catalogue gags is boring, so we reluctantly won’t do

so—other than to say the flow of same in this picture is abundant and

sustaining to the end. Also the boys manage neatly to clean up a few poolroom

jokes which have a particular subtlety, at least for the wise guys in the back.

Several songs are also brought into the picture by the Messrs. Crosby and Hope

and Miss Lamour in one or another combination, all of them handled pleasantly.

We understand this picture was made a few years

ago and is just now released. The reason? They were waiting till the

laugh-ceiling was off. Now look out for inflation. It will skyrocket laughter

throughout the land.

(Bosley Crowther,

New York Times, February 28, 1946)

The highly successful

Crosby-Hope-Lamour “Road” series under the Paramount banner comes to attention

once again in “Road to Utopia,” a zany laugh-getter which digresses somewhat

from pattern by gently kidding the picture business and throwing in unique

little touches, all with a view to tickling the risibilities. Very big

boxoffice results assured . . .

Though this one is rich in laughs and fast, the songs turned out for it are not

of heavy caliber. Crosby and Hope’s “Put It There Pal” is on the novelty side

and cute. Crosby single, “Welcome to My Dreams” and Miss Lamour’s number in a

saloon setting, “My Personality” is nothing to get excited over. Quite good,

however, is her “Would You.”

(Variety, December 5, 1945)

Gorgeous fun is provided by the

famous two of the former “Road” films. This one takes them to the frozen wastes

of Alaska, and is told in a flashback as the film opens with Bob Hope and

Dorothy Lamour an old married couple enjoying a visit from dashing old bachelor

Bing Crosby. Bob and Bing are entertainers who have to make a quick exit from

the port where they are performing, and pose as a pair of tough bad men, with

plenty of trouble resulting from their theft of a map. It is packed with bright

lines, comic situations, and unexpected laughs. Don’t miss it.

(Picture Show, December 29,

1945)

Mel Frank was

responsible for a “Utopia” line which became a movie classic. In ‘Road to

Utopia’, Hope and Crosby have to act tough to impress the local bad guys. They

saunter up to a bar in the mining town, and the local heavy asks, “What’ll you

have?”

“Oh, a couple

of fingers of rotgut,” growls Crosby.

“What’s yours?”

asks Douglas Dumbrille.

“I’ll take a

lemonade,” squeaks Hope in a high pitched voice before responding to a nudge by

Crosby and snarling, “in a dirty glass.”

(Randall G.

Mielke, Road to Box Office)

February 28, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Martha Tilton and

Jerry Colonna. A song from the rehearsal is issued on V-Disc.

March 7, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Lina Romay. Later,

having been nominated again for the Oscar as “Best Actor” for The Bells of

St. Mary’s, Bing loses out to Ray Milland (for his performance in The

Lost Weekend) at the Academy Awards ceremony at Grauman’s Chinese Theater. The

Bells of St. Mary’s has also been nominated as “Best Picture” but The

Lost Weekend is the winner. Similarly, Leo McCarey, who had been nominated

for “Best Director” for The Bells of St. Mary’s, loses to Billy Wilder

for The Lost Weekend. Ingrid Bergman is nominated as “Best Actress” for The

Bells of St. Mary’s but she is beaten by Joan Crawford for Mildred

Pierce. Robert Emmett Dolan’s nomination for “Best Scoring of a Dramatic or

Comedy Picture” is unsuccessful too as Miklos Rozsa wins for Spellbound.

Two of Bing’s songs (“Ac-cent-chu-ate the Positive” and “Aren’t You Glad You’re

You”) are nominated as “Best Film Song” of 1945, but the winner is “It Might As

Well Be Spring” from State Fair. Bing is supposed to sing his two songs

at the ceremony but he pulls out at the last moment.

March 8, Friday. The Crosby Investment Corporation

obtains a court injunction against Bing's brother Ted claiming that he had failed to live up to a contract agreement.

BING ENJOINS HIS BROTHER FROM SELLING STOCK

Washington, March 10. - Bing Crosby got a

temporary injunction in Federal District Court here Friday to prevent his

brother Ted from selling 100 shares of stock in Bing’s Del Mar Turf Club

(Daily Variety, March 11, 1946)

March 9, Saturday. Bing is

at Santa Anita to see War Knight win the Santa Anita Handicap in a

photo-finish.

March 10, Sunday. Starting at 1 p.m., Bing and Bob Hope tee off on the new Long Beach Naval Hospital

pitch and putt course. Jerry Colonna and Tony Romano are also in the foursome

whilst Frances Langford keeps the score. Bing has a 28, Hope a 29. A crowd of 3,000 watches the event.

March 13, Wednesday.

Ted Crosby says that he has been damaged to the extent of $10,000 by

the suit brought against him by the Crosby Investment Corporation. He

states that it is "an unfortunate family affair which has no place in

court."

March (undated). Has dinner with the Russell Havenstrites at the Beverly Hills Club.

March 14, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Frank Morgan guests. A song from the rehearsal is issued

on V-Disc.

March 16, Friday. Has tickets to hear soprano Marjorie Lawrence sing at the Philharmonic Auditorium but it is not known whether he actually attended.

March–May. Films Welcome

Stranger

with Barry Fitzgerald and Joan Caulfield. The director is Elliot

Nugent. Robert Emmett Dolan handles the musical score and Joseph J.

Lilley

looks after the vocal arrangements. Location shots are filmed at Munz

Lakes in the northern Sierra Pelona Mountains in Los Angeles County.

March 21, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Cully Richards and

the Slim Gaillard Trio. A song from the rehearsal is issued on V-Disc.

“I would stand in line only to see Bing

Crosby,” an out-of-town woman back of us was overheard to say as we waited for

NBC’s Studio B’s doors to open for Music Hall. I wonder if she thought the same

after the miserable performance he gave. Crosby didn’t seem to be putting

anything into his songs–not even good tonal quality at times. He should keep

two things in mind–the debt he owes the public for its loyalty and the fact

that one comes down hill much faster than one goes up. The perfect spot on

Music Hall was the song by the Charioteers. Eddy Duchin’s piano playing was

smooth, the comedy, mediocre. The Slim Gaillard Trio probably was more

interesting to see in action than it was to hear over the air. Its number was

novel, at any rate. There was a lack of warmth, a feeling of something being

missing from the Music Hall.

(Zuma Palmer, Hollywood Citizen News,

March 25, 1946)

March 22, Friday. (6:00–9:00

p.m.) Bing records "Oh, But I Do" and "A Gal in Calico" in Hollywood with John Scott Trotter and his

Orchestra but both songs are unsatisfactory and are not issued.

March 28, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Georgia Gibbs.

March 29, Friday.

The first day of the first peacetime baseball season for 5 years. Lieutenant Gov. Fred Houser was

supposed to waft the first pitch to Bing at Gilmore Field but bad weather prevents it

and it is rearranged for the next day.

March 30, Saturday. Starting at 8:15 p.m. Lieutenant Gov. Houser duly makes the first pitch to Bing. Later, Bing

and Dixie attend a party at the Clover Club on Hollywood Boulevard which is

hosted by Cary Grant, James Stewart, Eddy Duchin and John MacClain.

The four hosts,

all dressed in tails, formed a receiving line. Mike Romanoff’s food ranged from

green turtle soup to oysters, crab, shrimp, trout, chicken, stuffed turkey,

roast ribs of beef, ham, coq au vin, boned squab, vegetables and salads, and

numerous desserts. At five in the morning, 250 guests were still there, sitting

on the floor and listening to Bing Crosby sing every song he ever knew, to the

accompaniment of Hoagy Carmichael.

(Peter Duchin, writing in his book, A

Ghost of a Chance)

The last to go

home at eight a.m. were Bing Crosby and Pat O'Brien. Eloise, Pat’s wife, couldn’t come to

the party because of the expected baby — and when Pat saw what time it was, he

insisted that Bing come home with him.

(Modern Screen, July 1946)

March 31, Sunday. Bing and Leo McCarey help out at the Garden Charity Bazaar given by

Mrs. Bob Hope for Immaculate Heart College. They are put in charge of the religious booth

April 4, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Georgia Gibbs.

During the day, Bing and other stars send a telegram to Washington objecting to

a new bill intended to curb the activities of James C. Petrillo, president of

the American Federation of Musicians. They felt that it covered too much other

ground and would restrict the labor rights of all radio workers.

April 6,

Saturday. Dixie is

reported to be in hospital with the flu. Earlier press reports had

suggested that she was entering hospital for a major operation.

April 7, Sunday. Attends a garden fair and buffet supper at Bob Hope's home for the benefit of destitute children.

April 11, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Marilyn Maxwell and

the Les Paul Trio.

It’s now Prof.

Trotter, if you please. Music Hall’s plump and affable conductor is now

instructing a weekly class in radio orchestration at University of Southern

California. But he won’t let the dignity of his new title prevent his joining

Bing Crosby and Eddy Duchin in warm welcome to Marilyn Maxwell when the songstress

goes visiting at 9 p.m.

(The Miami Herald, 11th April, 1946)

April (undated). Bing

and Barry Fitzgerald are photographed receiving smallpox vaccinations

following reports of increasing cases of the disease in Hollywood.

April 15, Monday. Filming of

Abie’s Irish Rose commences. This is the second film made by Bing Crosby

Productions and it stars Joanne Dru and Richard Norris. Edward Sutherland is

the director and John Scott Trotter is in charge of the music. Everett Crosby

has not put proper financing in place for the film and at the outset they

cannot meet the payroll costs. Faced with this crisis, Bing hires Basil Grillo

to run Bing Crosby Productions. Grillo subsequently reorganizes all the Crosby

business activities and Bing Crosby Enterprises is formed. Everett Crosby’s

influence on his brother’s business matters recedes.

Everett was just about persona

non-grata over the “Abie’s Irish Rose” fiasco but he took Grillo to Paramount

and faced his brother down, the last of many significant things he did for Bing

Crosby.

The two

argued heatedly, during a break in filming, and enough of the conversation was

audible for Grillo to realize Crosby regarded him as merely the latest in a

long line of “geniuses” supposed to “fix everything.” As Grillo remembered the

scene, Crosby seemed abruptly to give in. He walked off the set and over to

where Grillo stood, extending his hand and offering an apology for the broken

appointments.

“He turned

on that friggin’ Irish charm and I was his forever,” Grillo said. The brief

meeting began a 30-year relationship and when it was over, Grillo would

describe Crosby as:

“The

finest human being I have ever known.”

“Abie’s Irish Rose” became Grillo’s first priority. Crosby was worried about

the situation finding its way into the newspapers and asked him to talk with

Sutherland whom he had known since his days at the Cocoanut Grove. Sutherland

also had directed him in “Mississippi” in 1935. The director agreed to proceed

without pay until financing could be put in place. Grillo then made the same

plea to Joanne Dru who also agreed. He telephoned the news to The Singer,

pointing out Sutherland and Dru’s cooperation did no more than win a little

time. He suggested the simplest solution might be for Crosby to personally

finance the picture. Crosby exploded and banged the phone in his ear.

Ultimately,

Grillo was able to negotiate a loan for $370,000 from Society First National

Bank of Los Angeles and the film about a Jewish boy and a Catholic girl was

released amid mild controversy in 1946.

(Norman Wolfe, Troubadour: Bing

Crosby and the Birth of Pop Singing)

April 17, Wednesday.

Completes the sale of his 35 percent interest in the Del Mar track for a

reported $481,000 and soon sells the home at Rancho Santa Fe and his stables.

His brother Ted sues him over the Del Mar sale. Elsewhere, Dixie Lee is named “Hollywood’s

Ideal Mother” by the advisory committee of the United Home Finding Service.

April 18, Thursday.

(11:00–2:00, 4:30–6:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Trudy Erwin and the

Kraft Choral Club.

Kraft Music Hall (review), NBC, Thursdays, 9

PM,

EST.

Well, Crosby’s back and Kraft has

got him--at least until May. After getting off to a somewhat dispirited start,

Bing has swung back into his free and easy method of entertaining, with

informality the keynote. He heckles the orchestra, the announcer, the guests,

and even makes fun of himself with well-timed ad libs that require more than

casual listening to catch all of the fun that goes on. His singing on the air

has improved since his vacation, even as it has on records; his backing from

John Scott Trotter and band isn’t as good as the Haggart, Heywood, etc. he’s

had on records, but he sounds as though he’s enjoying it and that produces fine

Crosby singing.

Regulars are the Charioteers who sing spirituals inoffensively, Eddy Duchin who

makes with a bit of comedy and some strictly unhep piano solos, Ken Carpenter

who plays straight man to Bing plus doing the commercials (accompanied by

remarks from Bing), and the fancy work of Les Paul, who occasionally rounds up

his trio for some really find plucking.

It’s

too bad if Bing is unhappy, as rumours riot, about a live show; it doesn’t seem

as though this spontaneity could be carried into a transcription studio and

come out equally merry. It’s anybody’s guess as to Bing’s sponsor for next

fall, but with Crosby at his best it should be mellow stuff.

(Metronome, May 1946)

April 20, Saturday. Decca has issued a 6-disc 78rpm album set by Bing called Don't Fence Me In and it reaches the No. 2 spot in Billboard's best-selling popular albums chart on this day.

April 21, Easter Sunday. Dixie Lee and

her four sons are in Carson City, Nevada during the morning on their way to Bing’s Elko

ranch. Mrs. Crosby and the quartet of hearty youngsters had breakfast at the

Senator and did some shopping. (12:00 noon–1:00 p.m.) Bing is on Can You Tie That, a radio program over station

KLAC which is emceed by Al Jarvis

and comes from Earl Carroll’s Theater/Restaurant in Hollywood. This is a record

grading contest. Bob Hope grades “Who’s Sorry Now” by Bing while Bing grades

Hope’s record of “Two Sleepy People” amongst several other records by other

artistes. The other members of the panel are Ella Logan and Dave Dexter. The

event is designed to generate funds for underprivileged people of the world and

$14,000 is raised.

The occasion was a

clothing drive for Catholic Charities, and the seven tons collected just about

measure up to the amount of hilarity served up on the discs. Hope and Crosby

jitterbugged their way through the first record played, Les Brown's "Good

Blues Tonight," and each gave it 95. Ella Logan judged it at 67, and Dave

Dexter granted it a tepid 59. At this announcement, Hope and Crosby got up to

leave. "You can tell we're from the country," commented Bob sadly.

Second record played was "Who's Sorry Now?" by a singer named Bing

Crosby. Crosby leaned back and listened in rapt attention with occasional

murmurings of "Beautiful—beautiful. Turn it up." Hope's first comment

was, "Well, I don't follow the singers much!" But he thought it was

nice that Eddie Heywood let his father sing with the band. "After careful

consideration, I give it six and one half points!" he decided. From singer

Shirley Ross, Jarvis borrowed an old record on which she and Hope shared the

vocal, "Two Sleepy People" (now scheduled for release). A stunned

Hope recovered to find that on nostalgia value alone even hard-to-get Dexter

had given him a satisfactory score. One of the highlights of the show was the

presentation to Crosby of a gigantic picture of Frank Sinatra. Bing countered

by giving Bob an even greater enlargement of Red Skelton. Jarvis admits that

throughout the program, the boys kept him laughing so hard that he forgot about

emceeing. "It should have been television," he sighed. "I've

never had so much fun in all my life!"

(Joan Buchanan, Radio Life, June 23, 1946, pages 7-8)

April 22, Monday. Bing

attends Bob Murphy’s annual Sportsmen’s dinner with his brother Larry, Bob Hope

and Joe E. Brown.

April 24, Wednesday. Bing is

part of a syndicate which files an application for a 1946–47 franchise in the

National Hockey League.

April 25, Thursday. Does not

appear on the Kraft Music Hall broadcast and is said to have gone to San

Francisco for a benefit performance. Frank Morgan deputizes for him. The book Bing

by his brothers Ted and Larry, which was originally published in 1937, is

brought up-to-date and republished as The Story of Bing Crosby

with a

foreword by Bob Hope. Ted Crosby is now shown as sole author. It sells

24,936 copies in the six months after publication, producing $450 in

royalties on top of a $2,000 advance.

May 2, Thursday.

(10:00–2:00, 3:30–5:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing returns to the Kraft Music Hall show on NBC. Guests include Joe

Frisco and Peggy Lee.

Bing Crosby, celebrating his

birthday on the Kraft Music Hall over NBC on Thursday night (2nd), came up with

one of the most hilarious shows in the soon to be concluded series. Evidently,

ad-libbing most of the way, Crosby broke up the show several times with aside

remarks to the studio audience and his guest stars, Peggy Lee and Joe Frisco.

The hilarity was topped during the last five minutes when Bob Hope appeared

unexpectedly with Bing’s birthday cake and the two let go with some unmatched

witticisms. Sore spot to some listeners occurred however, when the crooner went

off the deep end with a gag line to Eddy Duchin—“Fan your fanny over to the

pianny and waft some music this way.” It might have been better if Crosby,

heretofore, lauded for the cleanness of his shows and for “priest” roles he’s

portrayed in pictures had remembered that some parents object to their kids

listening to such stuff on the radio.

(Variety, May 8, 1946)

Selling records was only half of the equation for a popular singer in

Peggy Lee’s early

days. In postwar America, it was radio

that dictated the success of

records. No artist could be declared

major until she or

he appeared on a network

radio show. And no one had a network

radio show to rival

the Kraft Music Hall.

On May 12,

1946, (sic) Peggy Lee took to the NBC airwaves and sang “I Don’t Know Enough About You,” not only

for an immense audience—a few years earlier, the Kraft

show had boasted a staggering fifty million listeners—but

for the show’s host, the most beloved performer in the history of

American popular culture.

When

Peggy stepped in front of the microphone that night, it was

with the introduction and imprimatur

of Bing Crosby, the reigning

god of song. It was the first

of some fifty appearances she would make on

Crosby’s shows over the next decade, a time during which

Crosby would become a close

friend and ally. Crosby’s love for

Peggy Lee’s music,

and for Peggy

Lee the woman, was perhaps the single most important factor in the blossoming of her career—and how could it have been otherwise? As an artist, she was following a trail into pop-jazz that no woman had trod, but that Bing Crosby had not only discovered,

but mapped. It

was with Bing

Crosby’s sensibilities that Peggy Lee truly identified, on every band of the

spectrum.

(Fever – The Life

and Music of Miss Peggy Lee, pages 146-7)

Bing was always so protective and so

sensitive during my early days of nerves and self-consciousness. Just before

air time on one of my first Kraft programs, he found me standing rigid outside

the studio at NBC and asked me what he could do to help. I managed to say,

“When you introduce me, would you please not leave me out there on the stage

alone? Would you stand where I can see your feet?” From then on he always

casually leant on a speaker or piano to give me the support I needed to learn

about being at ease on stage.

You have to love a man like

that. He offered everything—money, cars, his own blood, and even volunteered to

babysit with our little daughter, Nicki, while David was so sick in hospital.

(Miss Peggy Lee—An Autobiography,

pages 105–106)

May 7, Tuesday.

(6:15–8:50 p.m.) Records four songs with John Scott Trotter and his Orchestra

in Hollywood, including “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” and “A Gal in Calico”.

The latter song reaches the No. 8 position in the Billboard Best-Seller lists,

spending six weeks in the charts.

A GAL IN CALICO. Bing Crosby, with the Calico Kids and John Scott

Trailer’s Orchestra Decca 23739. A bright and breezy rhythm ditty from the

movie “The Time, the Place and the Girl,” contagion is added to the chant in

the dittying design of Der Bingle who sings it free and easy, with vocal

assist from the Calico Kids to heighten the appeal of the spin. Flipover is

also from the same screen score, with Crosby chanting it alone and with

persuasion from the slow ballad “Oh, But I Do.”

(Billboard, December 7,

1946)

May 9, Thursday.

(10:00–2:30, 3:30–5:00 p.m.) Rehearses for his Kraft show. (6:00–6:30 p.m.)

Bing’s final broadcast as host on the Kraft Music Hall. The guests are

Dorothy Claire and Spike Jones and his City Slickers.

The

last airing (May 9) was a surprisingly subdued, if not to say mild, offering.

No fanfares, no frills, no balloons going up, no bells. After all those

hundreds of others, the listener might have expected something more appropriate

than (Ken): “Well, Bing, this is getaway night on the old Kraft Music Hall”:

(Bing): “That’s what it is, Ken.”

A bit

later, Duchin tells Bing, “I want to wish you a happy

vacation and - no kidding - thanks for everything.” At the moment before the

close, Bing speaks directly to his audience. “I want to thank you all from the

bottom of my heart for your tolerance and loyalty for this show.” This time,

the applause runs on and on, then under Ken’s sign-off. Trotter’s orchestra

carries all of it into yesterday with a few bars of the swing arrangement of

HAIL KMH!

(Vernon Wesley Taylor, Hail KMH! The

Crosby Voice, February 1986)

May 10, Friday. (5:00–9:00

p.m.) Records “Route 66” and “South America Take It Away” with the Andrews

Sisters and Vic Schoen and his Orchestra.

May 15, Wednesday.

(6:00–9:30 p.m.) Records “Pretending” and “Gotta Get Me Somebody to Love” with

Les Paul and his Trio.

It is a sad,

thankless, and sometimes presumptuous task to have to report that a champion

has slipped up. If the champ happens to be a great one—personally as well as

professionally—the task becomes inordinately difficult.

Bing Crosby has become that kind of champ. He has been the

non-pareil, the unprocessed cheese kid. From the days of “Just One More

Chance,” down through the abundantly talented years, he has been wonderful,

with a special kind of purity in his appeal. Of late, though, his seeming

disinterest has become more and more apparent, until now it can no longer be

ignored.

In the entertainment business, though, you think twice before you

criticize an idol, for if it is kind of amusing to say that so-and-so has a

clothespin on his nose, it is almost lese majeste to suggest that a Crosby is

not what he used to be. But be that as it may, the evidence is too stark.

The Groaner, although his manner still has that incomparable kind of

relaxation, no longer imparts the verve, the dash of his early disking, and if

you think otherwise, listen to his newest releases.

Crosby’s “Pretending” and “Gotta Get Me Somebody to Love” (Decca 23661)

are so inferior that you are apt to mistrust your own judgment when you hear

them for the first time. You are apt to suspect that something is wrong with

your phonograph. But you find out it isn’t your phonograph at all. Bing

is accompanied by Les Paul and his trio (an effective background) and the faces

should have been good. Five years ago, they might have been magnificent.

Both tunes (“Gotta Get Me” is from Duel in the Sun) are the lazy sort of

thing which Bing used to do better than anyone else. But he sings them so

indifferently that you cannot ignore the gloomy conclusion that Bing has

slipped. Sinatra, Haymes, Como, Buddy Clark and a few others are cutting him.

If it sounds unduly harsh on him to say this, it would be harsher on the others

to keep it quiet.

(George

Frazier, Variety, October 2, 1946)

…Sheer routine are Pretending

and Gotta

get me somebody to love from the film “Duel in the Sun“ (03800).

(The Gramophone,

December 1947)

Bing Crosby Named in Composer’s Suit

on Song “Pretending”

Don A. Marion, composer, today asked for return

of the song “Pretending,” claiming it had earned $250,000 since it was

illegally appropriated by two other song writers. Mario’s suit for an

accounting and an injunction, filed yesterday, also naming Bing Crosby and Andy

Russell, Kate Smith and recording and radio companies for singing and selling

the song without his permission. He said the song he composed in 1930 was

stolen from him by Al Sherman, listed on the published version as composer of

the melody, and Al Synes, credited with writing the lyrics.

(Hollywood Citizen News, January 7,

1947)

May 17, Friday. The Woman’s

Home Companion poll names Bing as the leading male film star. He is similarly

named for the next four years. Meanwhile, Bing finishes

prerecording songs for The Emperor Waltz.

May 17…The

morning was devoted to sets. Lunched at the commissary and went to the sound

stage where Bing recorded “The Kiss in Your Eyes” magnificently. He made eleven

takes of it, which is unusual for him. Usually he gets a song in three…

(From the

diaries of Charles Brackett, as reproduced in It’s the Pictures That Got

Small, page 289)

May 21, Tuesday.

Bing had planned to stay with Spike Spackman in Ketchum, Idaho for the

opening day of the fishing season on the Wood River but he is held up

in Hollywood by business and says he will not be able to get to Idaho

until June 1. Dixie and Mr. & Mrs. Eacret have been staying with

Mr. Spackman and they return to Elko.

May 31,

Friday. Joan Fontaine and Roland Culver arrive at Jasper Park to join the crew

filming The Emperor Waltz. Bing is still on holiday.

June 1, Saturday. Decca has issued a 4-disc 78rpm album set called Bing Crosby - Stephen Foster and Billboard reviews it on this day.

It was expected that sooner or later Bing Crosby would make

an album of Stephen Foster tunes. Crosby does full justice to the popular

composer’s music.

June 3,

Monday. Bing is at Hugh Bradford’s Alturas Lake Ranch at Hailey, Idaho and

he writes to Bill Morrow.

Dear Bill,

We leave here today for Spokane and

then on up to the location at Jasper Park. Had a great time here with Spike

& Dolly, the Eacrets, Ralph Smith and Vic Hunter. Quite a bit of ad-lib

drinking went on and yesterday, by noon, Spike was leaning back quite a bit. We

caught 80 red-fish yesterday morning and spent the afternoon dredging the

bottom with some choice ??? trying to shake up a big one, but no luck. Too

early I guess. I hope your plans have developed so you can come up to Nevada

and on up here about mid-June. Johnny has several places cased for you and the

Wild Horse Dam and the lake fishing will be available. Just phone or wire him

at Tuscarora where and when to meet you.

I

should hear something from Kapp by the time I reach Jasper and I hope, for the

benefit of all concerned, it is something favorable. If not we can apply some

pressure in the rite spot. The General Motors transcribed show is very hot rite

now for about September opening. I propose the following lineup.

Glen Wheaton - Producer

Bill Morrow - Writer

Trotter - Band & choir

Les Paul - guitar accompaniment,

occasional specialties.

Skitch Henderson - Piano solo and

accompaniment.

Charioteers, Specialties,

accompanist Peggy Lee, or some ?? with a similar delivery.

Crosby

This

will be a package arrangement with possibly first four shows live and maybe one

or two others during the year, at our option. It should be an easy show for you

to write - with Wheaton doing documentary material - and such guests as we use,

being of a type suitable for humor.

Jack

tells me he is going to Mammoth on the 15th., so you got yourself a nice

parley, Mammoth to Nevada to Sun Valley. I’ll see you probably around July 1st

and we can discuss the foregoing at that time.

Take

care of all the local grummet (?) in my absence.

Bing

June 4,

Tuesday. Bing

arrives in Spokane by car from Sun Valley, Idaho and complains about

the poor road conditions, having had four tire blowouts. He then calls

in at the Athletic Round Table

before playing a friendly game of golf at the Country Club with Roy Moe

(local

pro), Bud Ward, and Vic Hunter (a Hollywood advertising executive who

is

traveling with Bing). Subsequently, Bing is persuaded by the Athletic

Round

Table to stay on and play in a benefit golf match with Bob Hope later

in the

week as Hope will be putting on a show in the Gonzaga stadium on

Thursday.

June 5, Wednesday. Bob

Hope flies into Spokane during the evening and gets together with Bing

straightaway. They go into the Desert Hotel and entertain the Athletic Round

Table before Bob leaves to rehearse his show planned for the next night.

Bob Hope and Bing Crosby nearly put

the Athletic Round Table out of business last night—or at least they tried.

The

famed twosome showed up at the Desert Hotel club unexpectedly about 9, donned

waiters’ uniforms and went to work behind the bar.

“Anybody want a drink?” yelled Hope.

And

customers immediately swamped the bar. Crosby and Hope promptly started handing

away the club’s bottled goods—until the stock, at least all that was handy, was

exhausted. The two then took off the jackets, autographed anything from blank

checks to membership cards, and left.

(Spokane Daily Chronicle,

June 6, 1946)

June 6, Thursday. Bing

calls in at Gonzaga University and at the Athletic Round Table he joins in

briefly with the Gonzaga Quartet who are rehearsing. At noon, Bing is the guest

at a Gonzaga High School class of 1920 reunion at the Spokane Hotel. Starting

at 1:00 p.m., Bing and Bud Ward play Bob Hope and Neil Christian (the local

professional) at the Downriver golf course, Spokane, before a crowd of 2,500.

The match, which is designed to raise money for the PGA rehabilitation

fund, ends all-square and Bing has a seventy-six. Bing’s approach shot to the

ninth green strikes a spectator breaking his binoculars but otherwise not

causing any damage. Press reports indicate that Bing is suffering from a touch

of arthritis in his shoulders and has played golf just three times in the last

five months due to filming commitments. He is also said to be suffering from

laryngitis and is unable to sing. He goes on to dine that night at the Desert

Hotel with Mr. and Mrs. Bud Ward and others where he is photographed with the

Gonzaga Quartet.

June 7, Friday. Bing lands a 16lb Rainbow trout while fishing at Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho with Vic Hunter and then leaves for Jasper Park, Alberta.

June 8, Saturday (evening). Arrives in Jasper Park over the

Banff-Jasper highway to film The Emperor Waltz with Joan Fontaine,

Roland Culver, and Richard Haydn. The director is Billy Wilder with Victor

Young in charge of the musical score and Joseph J. Lilley handling the vocal

arrangements. Young is subsequently nominated for an Oscar for “Best Scoring of

a Musical Picture” in 1948 but loses to Brian Easdale for The Red Shoes.

Bing is paid $125,000 for the picture. The location scenes are filmed at Jasper

Park in five weeks during May / June. The weather is often too poor for filming

and this gives Bing the opportunity to play plenty of golf on the Jasper Park

Lodge course. In addition he fishes at Maligne Lake during the period in

question. Bing stays in the cabin called Squirrel’s Cage at the Jasper Park

Lodge during the filming. The studio work is completed in Hollywood by

September 20, with Bing working until 1:00 a.m. some nights because of a

threatened studio shutdown. The movie costs $4 million, some $1.2 million over

budget. Because of a backlog at the studio, the film is not released until May

1948.

June 8, Saturday (evening). Arrives in Jasper Park over the

Banff-Jasper highway to film The Emperor Waltz with Joan Fontaine,

Roland Culver, and Richard Haydn. The director is Billy Wilder with Victor

Young in charge of the musical score and Joseph J. Lilley handling the vocal

arrangements. Young is subsequently nominated for an Oscar for “Best Scoring of

a Musical Picture” in 1948 but loses to Brian Easdale for The Red Shoes.

Bing is paid $125,000 for the picture. The location scenes are filmed at Jasper

Park in five weeks during May / June. The weather is often too poor for filming

and this gives Bing the opportunity to play plenty of golf on the Jasper Park

Lodge course. In addition he fishes at Maligne Lake during the period in

question. Bing stays in the cabin called Squirrel’s Cage at the Jasper Park

Lodge during the filming. The studio work is completed in Hollywood by

September 20, with Bing working until 1:00 a.m. some nights because of a

threatened studio shutdown. The movie costs $4 million, some $1.2 million over

budget. Because of a backlog at the studio, the film is not released until May

1948.

“I did The Emperor Waltz

after coming back from the war, from Germany, where I was stationed in

Frankfurt…It came out in ’48. We held it back as long as we could. We shot it

in 1946, because I know that we were in the Canadian Alps, where I shot a lot

of stuff, and we were celebrating my fortieth birthday. And I had made two grim

pictures, Double Indemnity and The Lost Weekend…It came out of a

bravado gesture that I made in a meeting of the front office. They did not have

a good picture for Bing Crosby. And I just said, “Why don’t we just make a

musical?”

“But it was not really a musical, because a musical is a thing

where people, instead of talking, they sing to each other. The songs are plot

scenes, and they sing. And I started fumbling around there for a plot, and that

was kind of it, well, the dog, and it was just kind of ach. We had to go

to Canada with that thing, for the Alpines. It was supposed to pass as the

Austrian Alps, except there were many villages in the Austrian Alps. In Canada,

there was just snow. And we were not very happy with Joan Fontaine, she didn’t

have the part. We had nothing. I was just kind of improvising there. The less

time you consume in analyzing The Emperor Waltz, you know, the better.

There’s nothing to explain, there’s nothing to read into that thing. The

picture was just…nothing. We were doing kind of little tricks that a good

magician would have maybe been able to get something more out of than I did. I

just had come back from Germany, from the war, from the job that I was doing

there. And I was in the mood kind of to do something gay, and when they brought

up Crosby. I jumped in with this idea…it was a favor for Paramount. No good

deed goes unpunished.”

Crowe assesses The Emperor Waltz. “The movie is

fascinating today, almost riveting, in how aggressively un-Wilder it is. For

that reason, it stands alone and apart from all his other work. And still there

is a jewel: Crosby’s musical number, “The Kiss in Your Eyes.””

(Billy

Wilder, speaking to Cameron Crowe, Conversations with Wilder)

In the book Nobody’s

Perfect: Billy Wilder: A Personal Biography, Joan Fontaine is quoted as saying:

“Crosby wasn’t very courteous to me. I remember he

didn’t stand up when we were introduced. I thought “Poor Dorothy Lamour!”

This man didn’t have respect. Maybe he treated her better. There was never the

usual costar rapport. I never enjoyed his songs after working with him. I was a

star at that time, but he treated me like he’d never heard of me. I should have

brought my sarong. Crosby’s personality was what you might have expected from

the Emperor Francis Joseph. He was the Emperor of Paramount. Bing Crosby